Introduction

At Ably, we run a large scale production infrastructure that powers our customers’ real-time messaging applications around the world. Like in most tech companies, this infrastructure is largely software-based; also like in most tech companies, much of that software is deployed and runs in Docker containers.

As you might expect if you’ve been following the technology scene at all, the following question comes up a lot:

“So… do you use Kubernetes?”

This has been asked by current and potential customers, by developers interested in our platform, and by candidates interviewing for roles at Ably. We have even had interesting candidates walk away from job offers citing the fact that we don’t use Kubernetes as the reason!

This is also a question we ask of ourselves when planning our longer term infrastructure road map: should we use Kubernetes as our primary deployment platform at some point?

Why Kubernetes?

Kubernetes is the most widely known system for large scale orchestration of containerized software. While dissenting voices exist, it is still very much at the peak of its hype cycle – it can frequently feel like everybody’s running on Kubernetes, or at the very least everyone is talking about how they want to move everything over to Kubernetes. Mesos is rapidly fading in popularity, the less said about Docker Swarm the better, and if you are still deploying to plain EC2 instances, you might as well be feeding punch cards.

Kubernetes has a lot going for it. It was developed by engineers with serious large scale production workload experience, applying real-world proven techniques from Google’s Borg orchestration system. It has endless vendor support, and you don’t launch a software product these days without official Docker images and a Kubernetes deployment guide.

Somewhat surprisingly, not a lot is left of the original purpose Kubernetes inherited from its inspiration, Borg – that being turning a large pool of baremetal machines into a private cloud environment. Most Kubernetes deployments today seem to happen on virtual machines, most often on public cloud providers. The public cloud is where a major motivation comes in for many organizations deploying Kubernetes today: it is seen as a unifying API layer that makes multi-cloud deployments transparent for your DevOps people.

Even in a single cloud, the Kubernetes developer experience is commonly cited. Developers are already comfortable with Docker, and Kubernetes makes it easy to get the same container running in production. With namespaces, built-in resource management, as well as built-in virtual networking features, or services meshes, or both, it also allows deploying multiple interacting services maintained by different teams without stepping on each other’s feet.

What does Ably do instead?

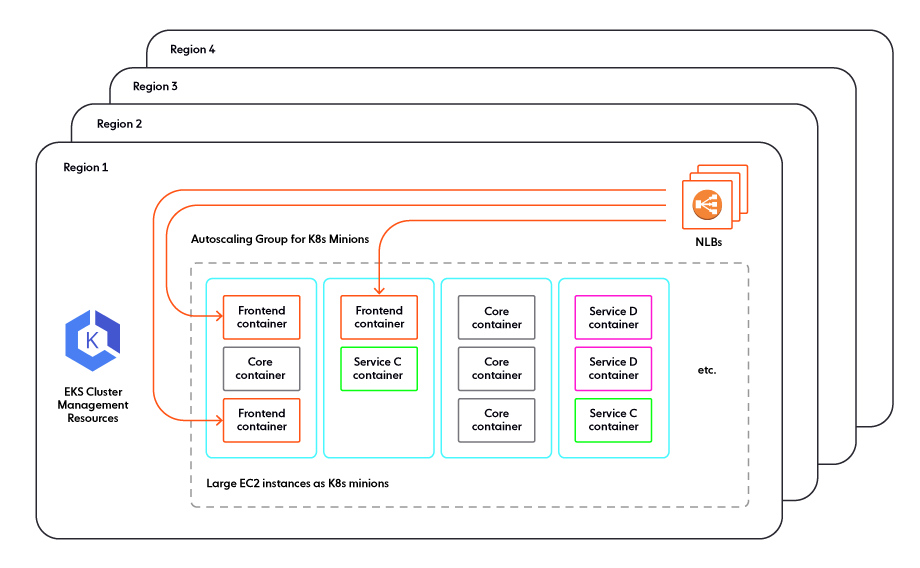

Ably is a public cloud customer. Our entire production environment exists on AWS and currently nowhere else. We run on EC2 instances. The total number of machines fluctuates with autoscaling throughout the day, but is always at least many thousands, across ten AWS regions. These machines do run Docker, and most of our software is deployed in containers.

What we don’t use is any of the well-known runtime orchestration layers. When created, each instance already knows which containers to run based on which autoscaling group it is in. A small custom boot service on each instance that is part of our boot image looks at the instance configuration, pulls the right container images, and starts the containers.

The set of containers is the same throughout the life of the instance. There is no scheduler service that may decide to convert an instance from a “core” into a “frontend” or anything else: to change the composition of the cluster, entire instances are created or destroyed, not told to run a different set of containers. There are lightweight monitoring services on each instance that will respawn a required container if it dies, and self-terminate the instance if it is running a version of any software that is no longer the preferred version for that cluster.

For traffic intake, we use AWS Network Load Balancers. Because one autoscaling group equals one production service, we can use the normal AWS method of pointing one NLB at one autoscaling group as the target group, with no additional abstraction layer required.

For internal service-to-service communication, or as the “service mesh” if you will, we use… the network. Because services are not arbitrarily mixed on machines, the machine’s automatically assigned IP address is plenty sufficient for our purposes.

Why Docker if you’re not going to use Kubernetes?

Docker is still a rather convenient format for deploying software, especially when it’s written in dependency-heavy languages (Node, Python, Ruby, …). In these situations, the deployable unit is thousands and thousands of interdependent files in complex directory trees, plus an execution runtime that needs to be the exact right version for that snapshot of the source tree.

We used to distribute our software builds as simple tarballs (we called them slugs, as Heroku does), with the management service on each instance downloading and unpacking them. Functionally, we still do the same, as Docker images are just a bunch of tarballs bundled with a metadata JSON blob, but curl and tar have been replaced by docker pull.

(Not everyone on the engineering team would agree that this is an improvement, but let’s leave that for another blog post.)

How flexible is this setup?

Resource management

When it comes to resource management, we can decide which EC2 instance type to use for a service based on its needs. There is no need to figure out how to pack smaller services onto larger instances, and figuring out how to pack small VMs onto large physical machines is something that Amazon have at least a decade more experience in than we do, so we let them sweat those details.

This is Right Sizing: most software services can only use a certain amount of resources effectively. A process with two threads doesn’t need 16 CPUs; a process that only writes to disk once a minute doesn’t need SSD storage with capacity for 90,000 writes per second; and alternative CPU architectures can be better value for money. Picking the right components out of the many AWS offerings allows us to minimize overhead and control costs, ultimately leading to lower per-message rates for our customers.

Autoscaling

EC2 instance groups know how to automatically increase or decrease the number of instances in the group to meet demand. The tooling available is similar to Kubernetes. Obviously, what we design for AWS is not directly going to work on any other cloud provider, but then we do not use any other cloud provider at this time.

Manual capacity management is, of course, still possible. The desired number of instances in each autoscaling group can be manually set at any time, and the autoscaling policies will take over again from there, adjusting the number up and down according to system load.

We only charge customers for how much they actually use the service. Any budget for spare capacity comes out of our pockets, so we need to be as efficient as possible here while guaranteeing a good service level for our customers even during unexpected load spikes.

Traffic Ingress

Specific implementation bugs we’ve encountered aside, traffic ingress is a solved problem on all major cloud providers – that is, as long as you can consistently map a service that accepts external traffic to the set of machines it is running on.

Customer traffic can either reach one of our NLBs directly, or first take a detour through CloudFront. From the perspective of services running within each region, it doesn’t make a difference.

In either event, using a load balancer in each region is another lever to enable horizontal scalability and flexibility – in this case to handle significant changes in the number of connections, such as when a big sports event starts and attracts spectators in the hundreds of thousands, or even more.

DevOps

To ensure our engineers can participate meaningfully in the management of our production systems, developers can set a single configuration value – “This cluster should be running this version of this component now, please” – and all instances of that service will be replaced by instances running the new version over time.

And with Kubernetes?

How would our environment and processes change (improve, hopefully) if we migrated production to Kubernetes?

Given the limited size of our Infrastructure Team, the only option worth considering would be managed Kubernetes with full AWS integration. With the around-the-globe deployment required by our product, we would need at least ten clusters (one for each of ten regions).

Resource management

When managing resources via Kubernetes, instead of using EC2 instances sized appropriately for each service, we would use large instances (possibly the largest available, in one of the .metal classes) and pack them with containers.

Packing servers has the minor advantage of using spare resources on existing machines instead of additional machines for small-footprint services. It also has the major disadvantage of running heterogeneous services on the same machine, competing for resources. This isn’t a new headache: cloud providers have the same problem – known as “noisy neighbors” – with virtual machines. However, cloud providers have a decade’s worth of secret sauce in their systems to mitigate this issue for their customers as much as possible. On Kubernetes, you get to solve it yourself all over.

One possible approach is to attempt to preserve the “one VM, one service” model while using Kubernetes. The Kubernetes minions don’t have to be identical, they can be virtual machines of different sizes, and Kubernetes scheduling constraints can be used to run exactly one logical service on each minion. This raises the question, though: if you are running fixed sets of containers on specific groups of EC2 instances, why do you have a Kubernetes layer in there instead of just doing that?

Autoscaling

When it comes to life with Kubernetes, autoscaling for the services would look fairly similar: expose a custom “current utilization” metric and have rules to add or remove containers as needed. Of course, the Kubernetes cluster would be able to launch additional service pods only as long as capacity is available on a cluster node. As such, we would need to deploy those with considerable spare capacity, and add a Cluster Autoscaler to make more nodes on demand.

Scaling the cluster up is relatively simple for the cluster autoscaler – “when there isn’t as much spare capacity as desired, add nodes”. Scaling down, however, gets complicated: you will likely end up with nodes that are mostly idle, but not empty. Remaining pods need to be migrated to other nodes to create an empty node before terminating that node to shrink the cluster.

The verdict on autoscaling is that it should still work similarly to how it does now, but instead of one autoscaling problem we would be solving two autoscaling problems, and they are both more complicated than the one we have now. On-demand or scheduled capacity management (manual intervention) would be a bit more complicated, as we would first have to ensure that there are enough Kubernetes nodes, and only then that there are enough pods for the required services.

Traffic Ingress

Traffic Ingress, for a change, would be refreshingly easy with Kubernetes. The EKS team has made some commendable design choices there: if the cluster is configured that way, each pod receives an AWS-managed IP address fully integrated with the VPC, EC2’s virtual networking layer. These IPs are directly reachable for things running inside the cluster, from things running on AWS in the same VPC family but outside the cluster, and through both kinds of AWS virtual load balancers.

There is a controller that will automatically create AWS load balancers and point them directly at the right set of pods when an Ingress or Service section is added to the Kubernetes specification for the service. Overall, this would not be more complicated than the way we expose our traffic routing instances now.

The hidden downside here, of course, is that this excellent level of integration is completely AWS-specific. For anyone trying to use Kubernetes as a way to go multi-cloud, it is therefore not very helpful.

DevOps

In a Kubernetes world, software version management would be functionally very similar to what we have now. Instead of specifying a new target version in our custom configuration system and all EC2 instances automatically going through rolling replacements, our developers would specify a new target version in a Kubernetes Deployment and the pods would go through rolling replacements.

But are there other benefits?

The previous section can be summarized as follows: we would be doing mostly the same things, but in a more complicated way. This could be worth it if there existed side benefits from running on Kubernetes that we haven’t considered when talking about how to port over our existing infrastructure. Let’s look at a few more things that are commonly cited as Kubernetes advantages and see if they would help us.

Multi-cloud readiness

Everyone should have a multi-cloud strategy!

We find ourselves in the “shouldn’t” group, and are currently not pursuing this strategy. We also don’t fully buy that Kubernetes is a good way of achieving this. As soon as a service needs to reach services outside its own cluster, or needs to be reachable from outside its own cluster, or uses any kind of persistent storage, the differences between the major cloud providers do matter, and Kubernetes does not succeed at abstracting them away to the point where your developers don’t have to care about them.

If you would still need a strategy to deploy to Kubernetes on AWS and another, similar but different one to deploy to, for example, Kubernetes on GCP, is it that much harder to have similar but different strategies to deploy to AWS and GCP without Kubernetes?

Hybrid cloud readiness

Managing a hybrid cloud or on-prem environment (or, in other words, managing your own physical machines) is a valid reason to deploy Kubernetes, in our opinion. Not coincidentally, it is also what Borg was originally designed to achieve. If we were ready to start building our own physical datacenters instead of consuming public cloud resources, what we would install in them would almost certainly be baremetal Kubernetes clusters.

The alternative would be to attempt to build a private cloud based on virtualization, which many organizations choose to do. However, we know from previous experience building that kind of environment that it is definitely not a cheap or easy option.

We are not ready to get started on our own datacenters, though. We still need to double in size several times before the benefits of owning our hardware would justify the cost of maintaining a physical infrastructure group in our engineering department.

Infrastructure as Code

Infrastructure as code is something we’re already doing, with CloudFormation and Terraform and our own custom tools. Writing YAML files for Kubernetes is not the only way to manage Infrastructure as Code, and in many cases, not even the most appropriate way.

Access to a large and active community

An often-stated benefit of using Kubernetes is that there’s a large community of users out there to share problems and advice. But you don’t need to run Kubernetes to have access to a large community of users and developers. There are many other aspects to cloud computing, and we are very actively involved in many of them. The community of technologists who use AWS is bigger than the community of Kubernetes developers and users, with considerable overlap. Many of the other technologies we deploy, like Cassandra, are also very popular. We’re not feeling lonely outside the Kubernetes crowd just yet.

A fact more uncomfortable to acknowledge is that in many cases, using a product with a big and rapidly growing community of users is not actually helpful. Several of the engineers in Ably SRE have worked on Kubernetes teams in previous roles, and the huge number of novice users can make it very difficult to find useful information on Kubernetes-related issues. Lots of people use Kubernetes, but in our experience very few understand it deeply, so troubleshooting through the community is much more difficult than you might think for something with such a large user base.

The substantial number of vendors pushing into this space also creates a lot of technical churn, with features in the Kubernetes core being added or changed at a rapid pace to accommodate new third party add-ons people are trying to sell. A big, active community is a blessing and a curse.

Added Costs of Kubernetes

Complexity. Oh, the complexity. To move to Kubernetes, an organization needs a full engineering team just to keep the Kubernetes clusters running, and that’s assuming a managed Kubernetes service and that they can rely on additional infrastructure engineers to maintain other supporting services on top of, well, the organization’s actual product or service.

For example, those AWS EKS services for networking and traffic ingress mentioned above and described as impressively well done? Those don’t come with EKS. You need to create an EKS cluster, and then install and configure those services on top of it. And then some more.

If we were to go down the service provider route, then that clearly takes some work away from us, but that comes with its own costs. We already talked about the technical churn created from such a vibrant Kubernetes market, and so moving from one vendor to another is far from trivial. Choosing a vendor is not a light choice and is itself a kind of architectural commitment.

This issue is not specific to the managed Kubernetes offering from AWS – the whole industry is like this. The point isn’t that the EKS team is doing a bad job, but rather that even with a truly well maintained managed Kubernetes setup, there is still so much to do to go from a basic cluster to a reliable production environment for your services.

Conclusion

Even though we acknowledge that Kubernetes is a well-designed product, we do not currently use it or plan to use it. It’s not that it never makes sense to deploy Kubernetes – it just doesn’t make sense for us, at this time.

After careful cost-benefit evaluation, it seems that introducing such an enormously expensive component would merely move some of our problems around instead of actually solving them.

In our opinion, it also doesn’t make sense for a lot of companies that are currently going all-in on Kubernetes, but that choice is up to them. If you’re reading this and your organization is currently trying to decide how much Kubernetes they need, we hope our perspective will help you make the right decision for your team.

Our production systems definitely suffer from problems and technical debt, much like anyone else’s. There is a list of improvements we’d like to make, and we’re hiring additional engineers to help make them. However, ultimately, “migrate to Kubernetes” is not on that list.

| Discuss this post on Hacker News |

Latest from Ably Engineering

- Key choices in AWS network design: VPC peering vs Transit Gateway and beyond

- Ably's globally-distributed architecture for reliable, low-latency edge messaging

- Stretching a point: the economics of elastic infrastructure ?

- Save your engineers' sleep: best practices for on-call processes

- Squid game: how we load-tested Ably’s Control API

About Ably

Ably is an enterprise-grade pub/sub messaging platform. We make it easy to efficiently design, quickly ship, and seamlessly scale critical realtime functionality delivered directly to end-users. Everyday we deliver billions of realtime messages to millions of users for thousands of companies.

Our platform is mathematically modelled around Four Pillars of Dependability so we’re able to ensure messages don’t get lost while still being delivered at low latency over a secure, reliable, and highly available global edge network.

Take our APIs for a spin to see why developers from startups to industrial giants choose to build on Ably because they simplify engineering, minimize DevOps overhead, and increase development velocity.